Exoplanet Detection and Characterisation

Developing instruments and using astronomical observations to detect and characterise exoplanets, in order to map the full diversity of planetary systems and search for planets which may host life.

Searching for and studying exoplanets — planets orbiting other stars than

the Sun is vital to place the Earth and the Solar System in their broader cosmic context, to map out the

full diversity of outcomes of the planet formation process, and to find out where else in our Galactic

neighborhood might be home to life. Oxford Physics is home to astronomers and planetary scientists who

use ground- and space-based telescopes to detect exoplanets, including (but not restricted to) those

that may host life, and study them in detail.

Exoplanets, particularly those that may host

life, are challenging to observe remotely, because they are small, faint and buried in the glare of

their host stars. Astronomers must use ingenious indirect techniques or extremely powerful instruments

to detect them. In Oxford we design and build instruments for the world’s largest telescopes and for

space missions dedicated to exoplanet characterisation. We are strongly involved in upcoming surveys

using the transit and radial velocity methods, particularly the European Space Missions’s PLATO mission

and the ground-based Terra Hunting Experiment, which aim to discover nearby Earth-analogues over the

coming decade. We use low and high-resolution spectroscopy from ground and space-based telescopes such

as VLT, ELT, JWST and ARIEL, to study the atmospheres of both giant and rocky planets in detail,

measuring their composition, structure, dynamics and variability. We develop and test strategies to

search for atmospheric markers of habitability and biological activity on distant exoplanets. We also

work with Breakthrough Listen, a privately funded initiative hosted by Oxford Astrophysics, to search

for radio and spectroscopic technosignatures on distant worlds.

Solar System Exploration

Systematically exploring the environments of worlds where life might exist — or once have thrived — within our Solar System, through a combination of theory, experiment, instrument development and spacecraft exploration.

Understanding where life can exist outside of the Earth cannot be achieved

without exploration. It informs on where conditions conducive to life might exist, and the individual

opportunities and challenges to life’s evolution each of these worlds presents. At the University of

Oxford, the Planetary Group conducts pioneering research into the origins, evolution, and potential

habitability of worlds across our solar system.

Our research combines planetary physics,

surface and sub-surface modelling of icy and rocky worlds, atmospheric chemistry and dynamics, and

advanced instrumentation development to investigate the fundamental conditions of worlds across our

solar system. This is achieved through the analysis of data taken by ground- and space-based telescopic

observations, instrument development and operations, and through collaboration with a range of

instruments/missions. The inhouse instrumentation development includes designing, building and

calibrating spectrometers, imagers, and detectors able to constrain surface and atmospheric environments

of worlds across the solar system. Our data collaborations extend to a range of spacecraft missions

(e.g. JUICE, Europa Clipper, Mars Express, Lucy, New Horizons, Cassini and more) and telescopic

observations (e.g. JWST) to cover our Moon, Mars, the atmospheres of the Gas and Ice Giants and the

surfaces of their icy moons (notably Enceladus and Europa), asteroids, comets, Kuiper Belt Objects and

beyond.

Planetary Climate

Studying the processes that govern the evolution of planetary climate over time in order to predict where environments that are conducive to the emergence and evolution of life persist throughout the universe.

Earth is the only known planet with abundant surface liquid water, which is

the primary requirement for the development of Earth-like life. Earth’s long-term habitability is

governed by intricate climate feedbacks that require an interdisciplinary and coupled understanding of

planetary atmospheres and geophysical evolution. We can study Earth’s climate and the broad range of

planetary climates by leveraging first-principles numerical simulations of fluid dynamics, radiative

transfer, and volatile cycling to interpret climate records, including geological proxy data for Earth

and satellite and telescopic observations for planets beyond Earth. The long-term goal of this study is

to place Earth’s climate in a galactic context and understand the fundamental mechanisms that regulate

planetary climate.

OPAL aims to ascertain the physical and biogeochemical processes that

govern the evolution of climate on Earth, paleo-Earth, Solar System planets and moons, and the diverse

panoply of exoplanets. To do so, we use a multi-disciplinary approach encompassing atmospheric dynamics,

radiative transfer, atmospheric chemistry, and geophysical evolution. This will enable us to assess

which planets can support the emergence and evolution of life, and better understand the co-evolution of

climate and life on Earth.

Geodynamics and Tectonics

Studying how planetary tectonics drives the recycling of materials and regulates the climate to create stable, habitable conditions that allow life to emerge and persist.

Earth is a tectonically active planet teeming with life, and has been for

many billions of years. By contrast, other rocky planets in our solar system show much less tectonic

activity and lack any evidence of extant or past life. It has thus been hypothesized by many researchers

that tectonics/planetary geodynamics and life evolved co-evally and are intricately linked together.

Understanding terrestrial and extraterrestrial tectonic processes is crucial for the search for life

beyond Earth, as these processes play a fundamental role in maintaining a planet’s habitability over

geological timescales. Plate tectonics drives the exchange of volatile components between the Earth’s

surface and interior, helping to stabilize the climate — a key requirement for sustaining liquid water

and, by conceivable extension, life. Ancient tectonic activity also generated a diverse set of

geological environments that are candidates for potential sites for the origin of life on Earth, and

could represent analogues for where life may have flourished on other rocky bodies in our solar system

and beyond. At Oxford, we combine field work with petrological modelling to understand Earth’s tectonic

activity, in the present and the deep past.

OPAL aims to understand how internal planetary

processes influence surface conditions, allowing us to assess which exoplanets may possess the dynamic

systems necessary to support life and making geodynamics a vital field in the broader search for

habitable worlds.

Planetary Materials

Deciphering Earth’s formative early history by measuring magnetic, isotopic, and chemical signatures in meteorites and ancient terrestrial samples.

The Earth is on a unique evolutionary pathway that has led to it becoming

the only known inhabited planet in the solar system. This pathway was initially set during Earth’s

formation and subsequent evolution throughout the Hadean and Archean (the first two billion years of

Earth’s history) until the rise of complex life. We can gain novel insights into these crucial time

periods by analysing both extraterrestrial and terrestrial samples. These samples include meteorites to

explore planetary formation, as well as ancient terrestrial samples to understand how conditions on the

surface have changed across our planet’s history. Samples are analysed using an array of techniques

including isotopic analysis, chemical analysis, paleomagnetism, and high-temperature–high-pressure

experiments. These approaches provide complementary insights into the timescales and processes involved

in planet building and early planetary evolution, such as core formation, the delivery of water, and the

shaping of an atmosphere.

OPAL seeks to improve our understanding of Earth’s formation and

early evolution by pushing the state-of-the-art using this multidisciplinary approach. Ultimately, this

will enable us to address questions such as why Earth appears to be uniquely habitable, and the

conditions available for the very earliest life forms.

Evolution and Energetics on Planetary Habitats

Working to understand how life evolved on our dynamic planet, to make predictions for where life might emerge and thrive across the Universe.

The emergence of life on a planet requires the presence of both suitable

‘biological building blocks’ and a conducive environment. But, as the natural history of our planetary

home shows, life once present may come to dominate the future evolution of a planet’s surface. Although

we cannot say exactly how, when, or where life emerged on Earth, we do know that it was present on

Earth’s surface over 4 billion years ago, and likely arose as liquid water interacted with the rocky

products of volcanic activity and planetary formation. The wonder of life is its adaptability; its

capacity to evolve, occupy new environments, and change the geological evolution of a planet’s surface.

On Earth, cyanobacterial waste products oxygenated our atmosphere, fundamentally altered the composition

of ancient seas, and led to significant mineral deposits of economically vital importance. Bacteria and

plants weather rocks and, in turn, deposit new rocks, the chalk and limestone of our buildings, and

mobilised elements that keep our sea alive. The complex interdependence between, on one hand, life and

the geological processes that allow transport of materials from the depths of our planet to the

biosphere, and on the other hand, the ability of modern life to adapt to even the harshest environments

are only recently becoming apparent. Although it is recognised that humans have the capacity to alter

our environment, we are just the most recent example of life’s four billion year experiment in

‘terraforming’ a planet.

Our scientific interests are almost as diverse as life itself; our

goal is to learn more about how our planet and life has co-evolved over geologic timescales. What might

this tell us of the probability of life in the Universe, the emergence of disease or the future

evolution of our planet?

Biometals and Chemical Habitability

Studying how life and availability of biometals interact, shaping the environment and influencing habitability.

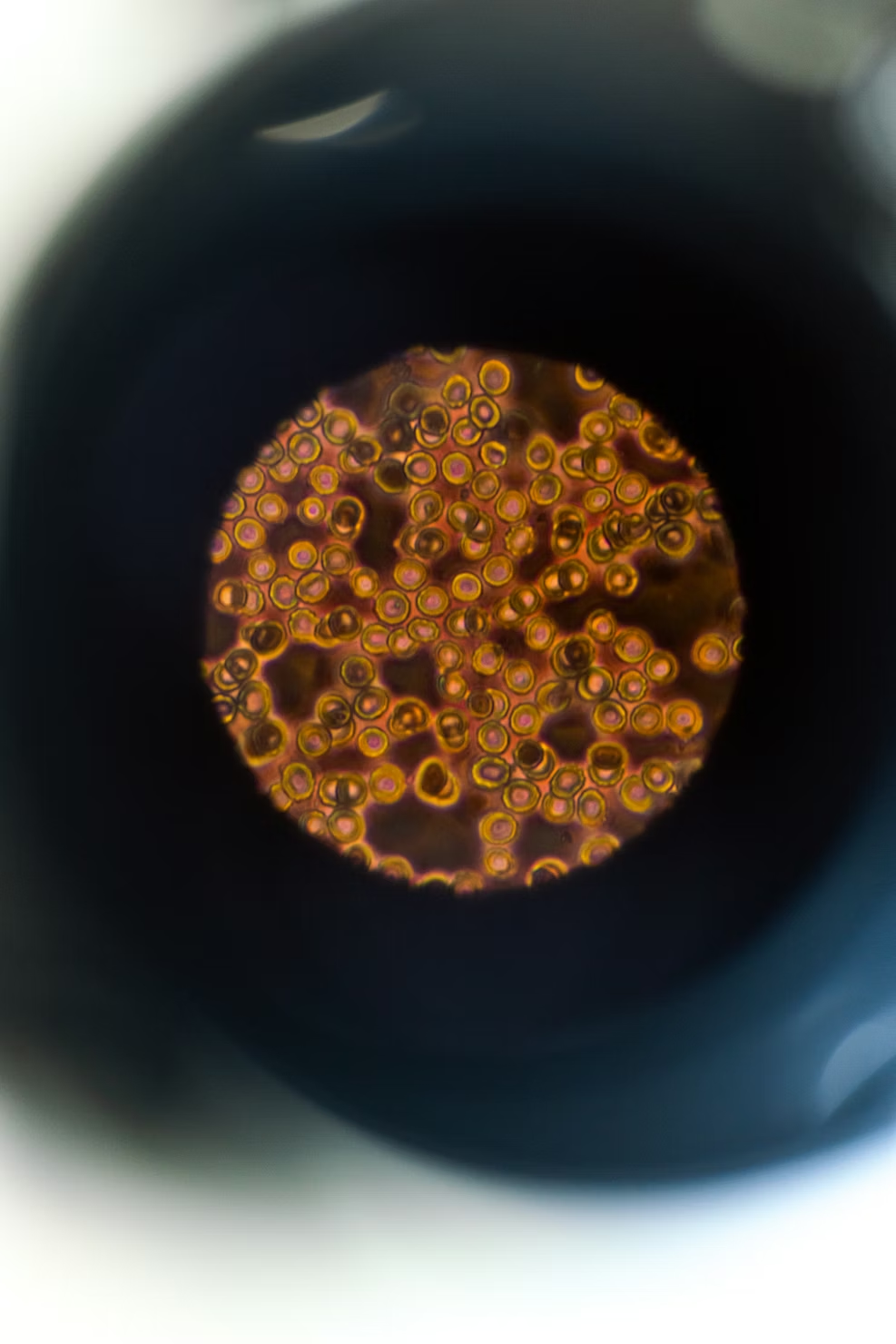

If we time-travelled to 3 billion years ago, we wouldn’t recognise our

planet as our home. The absence of oxygen meant the sky was a hazy orange and Earth’s seas, full of

dissolved iron, were green, and life on land was simply bacterial. This harsh environment is where

life’s basic biological ‘programming’ was defined. However, life itself then altered the biosphere, and

metals were key to this process. Nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis transformed biological

productivity, and, over time, changed the chemistry of the oceans and atmosphere. Metals, as critical

co-factors for enzymes (e.g., nitrogenases, hydrogenases) and processes (e.g., photosynthesis,

tricarboxylic acid cycle), were utilised as life developed. However, changes in the biosphere caused by

life, such as oxygenation, altered metal bioavailability (less iron, more molybdenum), generating huge

selection pressures and compensatory adaptations. ‘Battles’ for rare vital metal cofactors between

life-forms began, with ecological consequences. To understand these processes, we quantify and track

biometals in bacteria, algae and more complex organisms in experimental and field settings. We seek to

understand how metal co-factor availability for life influences planetary habitability.

OPAL

aims to study how metal availability shapes life, via effects on metabolism and biological processes,

that in turn affect the biosphere and influence evolution.